|

|

|

This

is the older third-half of this web site.

For

the latest current matierial, click

here.

July

30

Arbitration

Tilting More Against Investors

Commentary

by Jane Bryant Quinn

July

30 (Bloomberg) -- Let's say you had $50,000 in auction-

rate securities that your broker said were as safe as

money-market funds. The market collapsed and you sold

at an 80 percent haircut. At your arbitration hearing,

one of the three panel members works at a firm that

also sold auction rates deceptively. How fair will the

hearing be? Will the industry let this conflict of interest

stand?

The

flood of auction-rate claims against brokerage firms

points up, again, how badly the deck is stacked against

you in securities-industry arbitration. For claims exceeding

$50,000, your three-member panel of judges must include

an industry representative, plus two "public''

members who also can have industry ties.

The

industry rep is there to explain the industry's point

of view to the other panelists -- effectively, a Wall

Street mouthpiece, sympathetic to the very products

and practices you're complaining about. As an "expert,''

his or her opinion carries extra weight.

For

years, the lawyers representing customers have pressed

to get rid of this fifth-columnist on arbitration panels.

The industry always stonewalled.

Then,

in 2007, a bill called the Arbitration Fairness Act

appeared in Congress, containing a clause requiring

all three panelists to be from the public. Coincidentally

-- I'm sure -- the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority

(Finra), which runs securities arbitrations, decided

to hedge its position.

Last

week, Finra announced a two-year pilot project, allowing

as many as 420 cases to be heard by an all-public panel.

Customers' lawyers welcomed the pilot, tepidly, as a

baby step in the direction of fairness.

Then,

fairness got the boot.

Last

May, the Public Investors Arbitration Bar Association

wrote to Finra about the problem of conflicted panelists

on the auction-rate cases. PIABA President Laurence

Schultz, of Driggers, Schultz & Herbst in Troy,

Michigan, asked that potential panelists be excluded

from the hearings if they worked for firms that originated

or sold auction-rate securities. After private talks,

PIABA expected a yes.

Finra

said no, in a letter that Linda Fienberg, president

of Finra Dispute Resolution, sent to Schultz last week.

Arbitrators will simply be required to make additional

disclosures if, after Jan. 1, 2005, they worked for

firms that sold auction-rate securities, sold them themselves

or supervised anyone who did.

It

will then be up to the lawyers (or to the customers,

if they're representing themselves) to decide whether

to take those arbitrators as panelists. "The steam

is coming out of my ears,'' says Philip Aidikoff of

Aidikoff, Uhl & Bakhtiari in Beverly Hills, California.

To

understand the steam -- and why Finra is still being

pressed to change its mind -- you need to know how arbitration

panels are chosen. The parties to the dispute get three

lists of eight names, chosen randomly by computer from

the arbitrator pool. There's one list of industry panelists

and two for the two public members. Each side strikes

as many as four names on each list, for any reason at

all, then ranks the rest in order of preference. Finra

names the panel, choosing the arbitrators most acceptable

to both sides.

By

keeping the people involved with auction-rate securities

in the panelist pool, Finra forces customers' lawyers

to use up their challenges to get rid of them. If four

challenges aren't enough, they're stuck.

They

will also use up challenges that might have been needed

for other reasons, such as bouncing an arbitrator whose

awards consistently skew in favor of the industry. Arbitrators

can also be challenged for cause -- meaning direct and

definite bias or interest in the outcome -- though that's

hard to show.

What

makes this especially unfair is that arbitration issues

have changed, says Brian Smiley of Smiley Bishop &

Porter LLP in Atlanta. "The cases used to be about

isolated broker misconduct,'' he says. "Now we're

seeing institutional misconduct -- the perversion of

Wall Street research during the tech bubble, selling

fraudulent and unsuitable variable annuities, abuses

in the securitization of subprime products and, lately,

auction-rate securities.'' All the big firms are involved.

Say

that you have an auction-rate case against UBS AG and

get stuck with a Merrill Lynch & Co. branch manager

as your required industry panelist. How can that Merrill

manager bring in a large award, or indeed any award?

His own firm is up against the same charges. He might

worry that if he finds for you, it could cost him his

promotion or even his job.

Whatever

the reason, the win rate for consumers has been spiraling

down. They won 53 percent of their arbitrated cases

in 2001 but only 36 percent in 2007, according to the

Securities Arbitration Commentator in Maplewood, New

Jersey, which tracks awards. (So far this year, they're

running at 47 percent, says SAC Managing Editor Richard

Ryder.)

Even

with wins, you don't get much money back. In a study

of arbitration covering 1995 through 2004, attorneys

Daniel Solin and Edward O'Neal, of the Securities Litigation

& Consulting Group in Fairfax, Virginia, combined

win rates with awards to create an "expected recovery

rate.'' It peaked in 1998, at 38 cents on the dollar,

falling to 22 cents in 2004.

More

cases settle than go to arbitration, but those low recovery

rates "knock down the settlement offers you get,''

says attorney Theodore Eppenstein of New York.

When

trying to remove Wall Street's thumb on the scale during

arbitration, "you're up against some of the best

funded lobbying in the country,'' Aidikoff says. "Where

are the people who speak for individual investors?''

Where, indeed.

(Jane

Bryant Quinn, a leading personal finance writer and

author of "Smart and Simple Financial Strategies

for Busy People,'' is a Bloomberg News columnist. She

is a director of Bloomberg LP, parent of Bloomberg News.

The opinions expressed are her own.)

To

contact the writer of this column: Jane Bryant Quinn

in New York at jbquinn@bloomberg.net

August

1 , 2008

NY

AG to sue Citigroup units over auction-rate securities

by Chad Bray of

DOW JONES NEWSWIRES

NEW

YORK (Dow Jones)--New York State Attorney General Andrew

Cuomo said Friday he intends to "imminently"

take legal action against two Citigroup Inc.

units over their marketing and sales of auction-rate

securities.

In a letter Friday, Cuomo's office indicated it intended

to sue Citigroup Global Markets Inc. and Smith Barney

under the state's Martin Act for fraudulent marketing

of the securities and for destruction of documents under

subpoena.

Cuomo's office said a five-month probe found that Citigroup

"repeatedly and persistently" made material

misrepresentations and omissions in its underwriting,

distribution and sale of auction rate securities.

"Citigroup represented that auction-rate securities

were safe, liquid, and cash-equivalent securities,"

wrote David A. Markowitz, chief of Cuomo's Investor

Protection Unit. "These representations were false,

and had a severe detrimental impact on tens of thousands

of Citigroup customers."

Citigroup would become the third major Wall Street firm

to face legal action over its sales of auction-rate

securities in recent weeks.

Last week, Cuomo sued two UBS AG units

for allegedly misrepresenting to clients the risks of

auction-rate securities before the $330-billion auction-rate

market seized up earlier this year.

Massachusetts regulators filed charges against UBS in

June. On Thursday, they filed a civil-fraud complaint

against Merrill Lynch & Co. for

allegedly misrepresenting the nature of the securities

to investors and for co-opting its "supposedly

independent" research analysts to help them reduce

its own inventory of the securities.

A Citigroup spokesman didn't immediately return a phone

call seeking comment Friday.

Auction-rate securities are long-term bonds that have

a short-term debt component, in which interest rates

are reset in auctions on a periodic basis, including

daily, weekly or monthly sales. The bonds typically

are issued with 30-year maturities, but the maturities

can range from five years to perpetuity.

In February, several auctions failed, driving up the

interest rates for such issuers as municipalities, student-loan

providers and museums. The collapse of the auction market

also left investors locked into those investments.

In its letter, Cuomo's office said the Citigroup units

destroyed recordings of telephone conversations concerning

the marketing, sale and distribution of those securities,

which Cuomo had sought in an April 14 subpoena.

The letter said Citigroup failed to notify the attorney

general's office about the destruction of the tapes,

even though it learned in mid-June that recordings from

its auction-rate desk had been destroyed.

The attorney general's office said in the letter that

it didn't learn of the destruction of the recordings

until June 30 and it "significantly and materially"

interfered with its probe.

"Citigroup has informed the Attorney General's

Office that it is likely unable to recover the lost

information on the destroyed tapes," Markowitz

wrote.

"Verbatim records of the most important witness

statements during the most relevant period were therefore

destroyed after the issuance and service of the subpoena."

Cuomo's

office did leave the door open for a settlement with

Citigroup, saying in the letter the company must buy

back retail investors' securities at par; reimburse

retail investors for damages they have incurred; undertake

immediately to make institutional investors and corporations

whole; and pay a significant penalty for its alleged

misconduct during the investigation.

The New York attorney general's office has now subpoenaed

30 entities and 100 individuals, seeking information

about the sales of auction-rate securities.

Among those subpoenaed are Merrill Lynch & Co. By

Chad Bray, Dow Jones Newswires; 212-227-2017; chad.bray@dowjones.com

August

1, 2008

Merrill

'Co-Opted' Analysts Backed Auction-Rate Debt to the

End

By

David Scheer

Aug.

1 (Bloomberg) -- Four days before Merrill Lynch &

Co. stopped supporting the auction-rate securities market

and left thousands of individual investors stuck with

securities they couldn't sell, the firm's analysts recommended

clients buy.

"Reports

of the imminent demise of the auction market seem to

be greatly exaggerated, again,'' analyst Kevin Conery

wrote in a Feb. 8 research note. "We continue to

be impressed by the auction market's resiliency.''

The

remarks show Merrill's researchers were "co-opted''

during a seven-month drive by the New York-based firm's

sales force to prevent a meltdown in the $330 billion

market, Massachusetts Secretary of State William Galvin

alleged yesterday in an administrative complaint filed

in Boston. As the sales desk pushed analysts to publish

upbeat notes, managers used gallows humor to complain

about a "collapsing'' market and the end of $2,000

dinners.

"Come

on down and visit us in the vomitorium!!'' the auction-rate

desk's managing director, Frances Constable, wrote to

a co-worker in August, as demand began to dry up. "Market

is collapsing,'' another executive cited in Galvin's

complaint said in a November 2007 personal e-mail. "No

more $2K dinners at CRU,'' a Manhattan restaurant where

the wine list includes dozens of bottles for more than

$1,000.

Galvin,

57, wants the third-largest U.S. securities firm to

"make good'' on sales of now-frozen holdings, compensate

investors who disposed of their bonds or shares at a

loss and pay an unspecified fine. He has already filed

a related claim against Zurich-based UBS AG, and is

probing Bank of America Corp.

'Significant

Danger'

"Research

analysts routinely soft-pedaled significant negative

events affecting liquidity in the auction markets,''

he said in the complaint. At the same time, managers

knew "the auction markets were not functioning

properly and were in fact in significant danger of collapsing,''

he said.

Conery,

47, received a "six-figure'' bonus for 2007 after

his year-end review credited him for "proactive

and timely interchange'' with the sales desk and clients,

according to the complaint. "Ultimately, his work

contributed to better liquidity and lower inventory

levels in the marketplace,'' the reviewer said.

Merrill

denied that its analysts acted improperly in recommending

auction-rate securities, also known as ARS.

The

analysts mentioned in Galvin's complaint "are men

of integrity and intellectual honesty. They called the

ARS market as they saw it, not the way anyone else did,''

Merrill spokesman Mark Herr said. "Nothing the

sales desk could do or couldn't do affected how much

these analysts earned or their standing in our research

department.''

Pulling

Support

Auction-rate

securities are long-term bonds or preferred shares with

interest rates adjusted typically every seven, 28 or

35 days through a dealer-run bidding process, providing

them with the characteristics of money-market investments.

Firms historically supported the auctions, without contractual

obligation, when demand waned.

Merrill

is the second bank to face a complaint by Galvin after

brokers stopped supporting the auctions in mid-February

as losses from securities tied to subprime mortgages

mounted. Massachusetts last month filed a complaint

against UBS, Switzerland's biggest bank.

UBS

said it will contest the allegations. The bank agreed

July 30 to pay $1 million to settle a separate complaint

filed by Massachusetts Attorney General Martha Coakley

over the marketing of auction-rate securities to 20

towns and public agencies in the state. UBS also agreed

to pay $38.5 million to the municipalities.

Insurer

Losses

February's

meltdown began in July 2007, when MBIA Inc. and Ambac

Financial Group Inc., the two largest insurers of auction-

rate debt, reported lower profits because of losses

on securities backed by subprime mortgages. Losses at

the insurers prompted auctions for $1.8 billion of their

own securities to fail, according to Fitch Ratings.

That

month, Constable, 51, objected to an analyst's report,

which noted auction-rate bonds lack a so-called "hard

put,'' like some other variable-rate securities, which

obligate the issuer to arrange a purchaser for any unwanted

securities when rates reset.

The

reference was misleading, she said, because the report

focused on municipal bonds and those instruments weren't

yet failing. When the analyst, Martin Mauro, refused

to retract the note, Constable sent an e-mail to colleagues

within the firm.

"I

HAD NOT SEEN THIS PIECE UNTIL JUST NOW AND IT MAY SINGLE

HANDEDLY UNDERMINE THE AUCTION MARKET,'' she wrote in

capital letters, according to Galvin's claim.

'Misplaced'

Concerns

The

research department withdrew the report a day later,

Galvin said. While a revised version still included

information on the hard put, it also recommended auction-rate

securities, saying concerns were "misplaced'' and

they may offer good value.

"The

same facts contained in the first report were all retained

in a longer, fuller and clearer version,'' Herr said.

Constable,

Conery and Mauro, all located in New York, have no comment,

he said, declining to make them available. They aren't

named as defendants in Galvin's complaint.

Constable's

objections had a lasting effect, according to Galvin.

When an analyst drafted a report on the securities the

following January, he asked his colleague for advice

before publication.

"I

want to make sure that research cannot be accused of

causing a run on the auction desk,'' the analyst, who

wasn't named, wrote in an e-mail.

To

contact the reporter on this story: David Scheer in

New York at dscheer@bloomberg.net.

Last Updated: August 1, 2008 00:01 EDT

Updated:

Thursday July 31, 2008 17:36 EDT

Merrill

Defrauded Auction-Rate Investors, State Says (Update5)

By

David Scheer and Jeremy R. Cooke

July

31 (Bloomberg) -- Merrill Lynch & Co. was accused

by Massachusetts Secretary of State William Galvin of

misleading investors about the stability of the auction-rate

market at the same time the investment bank was marketing

the securities.

New

York-based Merrill "co-opted'' its research department

to help place the securities with customers, Galvin

said in a statement from Boston today. The state's administrative

claim asks the third-largest U.S. securities firm to

"make good'' on sales of now-frozen holdings, compensate

investors who disposed of their bonds or shares at a

loss and pay an unspecified fine.

"This

company was aggressively selling'' the securities "and

its auction desk was censoring the research analysts

to make sure they downplayed'' risks in the market,

Galvin said in the statement. "They knew the auction

markets were in trouble, but the investors were the

last to know.''

Merrill

is the second bank sued by Galvin after Wall Street

brokers abandoned their routine role as buyers of last

resort for auction-rate securities in mid-February,

allowing the $330 billion market to collapse. Massachusetts

last month filed a complaint against UBS AG, Switzerland's

biggest bank. A related investigation of Bank of America

Corp. is "still going on,'' said Brian McNiff,

Galvin's spokesman.

Auction-rate

securities are long-term bonds or perpetual shares with

interest rates adjusted typically every seven, 28 or

35 days through a dealer-run bidding process, providing

them with the characteristics of money-market instruments.

Firms historically supported the markets, without contractual

obligation, when demand dried up.

Market

Size

Municipal

auction-rate bonds totaled about $166 billion at the

time of the market's collapse in February; student-loan-backed

debt and closed-end mutual funds' preferred shares comprised

most of the rest.

Officials

in at least 12 U.S. states are investigating auction-rate

sales practices after receiving complaints from investors

unable to access their cash. New York Attorney General

Andrew Cuomo last week sued UBS, alleging the bank's

promotion of auction-rate securities as safe investments

was fraudulent.

One

of two former Credit Suisse Group AG brokers suspected

in a federal probe related to auction-rate securities

may have fled to his native Bulgaria, the Wall Street

Journal reported.

"In

September 2007, two former employees resigned after

we detected their prohibited activity and promptly suspended

them,'' said Regula Arrigoni, a Credit Suisse spokeswoman.

``Credit Suisse immediately informed our regulators

and we continue to assist the authorities.''

Congressional

Hearing

U.S.

House Financial Services Committee Chairman Barney Frank

said today his congressional panel will hold a hearing

in September to find out what went wrong in the collapse

of the auction-rate securities market.

Merrill

decided to stop supporting bids on auction-rate bonds

with its own money five days after one of its analysts

told financial advisers the bonds represented "a

good, conservative, reasonable investment,'' according

to Galvin's release.

"Our

research reflected the honest belief that'' auction-

rate securities "offered higher returns in exchange

for less liquidity and noted that market changes had

begun to occur,'' said Mark Herr, a spokesman for Merrill.

"We are disappointed that Massachusetts filed this

action.''

The

amount of auctions that failed to draw enough bidders

during two decades of the auction-rate market was "small,''

Herr said. "In 2007, there were no failed auctions

of securities sold to retail clients and, in fact, none

to these clients until late January 2008.''

Failed

auctions, where issuers' interest costs reset to a penalty

rate as high as 20 percent or pegged to a money-market

formula, have since become more common than successful

ones.

Profitable

Segment

Merrill,

which trails Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and Morgan Stanley

in market value, made about $90 million in profit during

2006 and 2007 from its auction-rate program, Galvin

said.

One

executive cited in Galvin's complaint said in a November

2007 personal e-mail: "Market is collapsing. No

more $2K dinners at CRU,'' a Manhattan restaurant where

the wine list includes dozens of bottles for more than

$1,000.

"Time

after time, when confronted with conflicts of interest,

Merrill Lynch was consistent in that it placed its own

interests ahead of its investor clients,'' according

to the secretary of state's complaint.

Biased

Research

During

the dot-com boom that peaked in 2000, Merrill was among

firms accused of publishing tainted research to promote

Internet companies. Through Henry Blodget and other

technology analysts, Merrill issued reports urging investors

to buy shares of companies such as 24/7 Real Media Inc.

and Interliant Inc. The value of 24/7 shares fell from

a peak of $323.13 in January 2000 to 45 cents by September

2001; Interliant peaked at $54.44 per share in February

2000 and reached 13 cents by May 2002.

Regulators,

including the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

and then-New York Attorney General Eliot Spitzer, accused

the investment banks of using the biased research to

lure investment-banking clients. Merrill, Citigroup

Inc. and eight other securities firms agreed to pay

$1.4 billion to settle the matter in 2002.

According

to the complaint Galvin released today, Merrill's sales

and trading department pressed the firm's analysts to

endorse auction-rate securities and took them to task

over their reports and conference calls. Year-end employment

reviews for some analysts evaluated how much support

they gave to ``business partners'' on the firm's auction-rate

desk, he said.

Research

Report

In

one incident, Frances Constable, the desk's managing

director, objected to an analyst's report in August

2007 that noted auction-rate bonds don't have a so-called

``hard put,'' like variable-rate demand notes, which

obligate the issuer to arrange for buying any unwanted

securities when rates reset.

The

reference was misleading, she argued, because the report

focused on municipal bonds and auctions for those instruments

weren't yet failing. Researchers rewrote the piece,

Galvin argued.

"In

fact, there were no material changes in the reports,

and the same facts contained in the first report were

all retained in a longer, fuller and clearer version,''

Herr said. "These two analysts are men of integrity

and intellectual honesty. They called the ARS market

as they saw it, not the way anyone else did.''

That

same month, Constable sent messages to an analyst during

a conference call with financial advisers. After a participant

asked a question, she urged the analyst to ``shut this

guy down,'' adding: ``He is focusing attention away

from your positive message.''

The

objections had an effect, Galvin said. In January, one

researcher asked if someone could review his work before

publication to ensure it wouldn't upset the auction

desk.

Constable

wasn't named as a defendant in the complaint. A call

to her office was referred to Merrill's spokesman, Herr,

who said Constable had no comment.

To

contact the reporters on this story: David Scheer in

New York at dscheer@bloomberg.net, or Jeremy R. Cooke

in New York at jcooke8@bloomberg.net.

Mass

charges Merrill Lynch with fraud in auction Rate Securities

Dealings

To

read the offical complaint and see the exhibits, go

to the Securities

Division, of William Francis Galvin, Secretary

of the Commonwealth

If

you can't read the PDFs posted on Mass site, go to Adobe

and pick up the latest version of Adobe

Reader.

Here

is today's official press release from Galvin:

Secretary

of the Commonwealth William F. Galvin today charged

Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith, Inc. with

fraud in pushing the retail sale of auction rate securities

to investors while misstating the stability of the auction

market itself.

The administrative complaint also charged Merrill Lynch

with co-opting its supposedly independent research department

to help sell auction rate securities.

The complaint seeks to order Merrill Lynch to make good

on the sales of ARS that are now frozen and make restitution

to those who had to sell at less than par.

The order would also censure the firm and impose an

administrative fine.

"This company was aggressively selling ARS to investors

and its auction desk was censoring the research analysts

to make sure they downplayed ARS market risks in research

reports up to the day Merrill pulled the plug on its

auctions," Secretary Galvin said. "They knew

the auction markets were in trouble, but the investors

were the last to know."

Today's complaint is the second action brought by the

Securities Division in the wake of the collapse of the

auctions earlier this year. Last month, a similar complaint

was brought against UBS.

At Merrill Lynch, the managing director in charge of

the auction desk got a research report in the Merrill

Lynch Fixed Income Digest retracted and rewritten. She

said the offending report "may single handedly

undermine the auction market."

The

complaint charges that "Merrill Lynch also permitted

Sales and Trading managers, including auction desk personnel,

to communicate to members of the Research Department

(in violation of company policies and procedures) sensitive

confidential information concerning inventory levels,

marketing initiatives, and enhanced sales incentives

offered to financial advisers.

Year-end employment reviews of certain Research Analysts

also took into account the level of support that analyst

provided to his 'business partners' at the Auction Desk."

Despite these efforts, Merrill Lynch, as the complaint

states, "had known for a period of several months

that auction markets were not functioning properly and

were, in fact, in significant danger of collapsing."

On November 19, 2007, one executive in a personal e-mail

stated, "Market is collapsing. No more $2k dinners

at CRU," referring to a Manhattan restaurant.

On February 7, 2008, Merrill Lynch Research Analyst

Kevin Conery told financial advisers, "But is it

(the auction business) an area we think represents a

good, conservative, reasonable investment? Yes, it is."

Five days later, Merrill Lynch decided to stop supporting

the auction rate securities program and most of their

auctions failed the next day.

The complaint further charged that the very process

of the auctions was "fundamentally flawed"

with Merrill Lynch submitting support bids to prop up

the market. "Broker-dealer support created a false

impression that there were deep pools of liquidity in

the auction market," the complaint said.

Merrill Lynch made about $90 million in profit from

this program in 2006 and 2007, but their dual role in

representing bond issuers and investors buying ARS "created

significant and inherent conflicts of interest which

could not be reconciled," the complaint said. "Time

after time, when confronted with conflicts of interest,

Merrill Lynch was consistent in that it placed its own

interests ahead of its investor clients."

Saturday

July 26

UBS

Suspends Top Executive

By LIZ RAPPAPORT of the Wall Street Journal

Swiss

bank UBS AG suspended David Shulman, the firm's head

of fixed income in the U.S. and global head of municipal

securities, according to people familiar with the matter.

The

suspension comes as state and federal investigations

have heated up into sales and marketing practices related

to auction-rate securities by UBS and other Wall Street

firms. Mr. Shulman ran the auction-rate securities business

at UBS.

The

office of New York state Attorney General Andrew Cuomo

on Thursday followed Massachusetts state securities

officials by filing a civil-fraud lawsuit against UBS

regarding its sales of auction-rate securities. Neither

has charged any individual, though Massachusetts named

Mr. Shulman as a figure who helped to direct UBS's efforts.

A

UBS spokeswoman confirmed the firm placed an employee

on administrative leave last week. The suspension occurred

in mid-July.

Mr.

Shulman is cooperating fully with UBS as it works through

these matters, said Jonathan Gasthalter, a spokesman

for Mr. Shulman.

Both

New York and Massachusetts suits allege that UBS and

its executives knew the auction-rate securities market

was collapsing last year and early this year, and didn't

disclose the problems to investors. Instead, the suits

allege, the firm marketed the securities to institutional

and retail investors through its sales forces to clean

their own inventories of the investments.

According

to the Massachusetts case, Mr. Shulman helped to direct

those sales. The case names several other UBS employees

and made public reams of their emails.

A

spokeswoman said UBS is frustrated by the cases because

the firm is working to help its clients holding auction-rate

securities. She said the firm doesn't believe any of

its employees acted illegally, but some might have used

poor judgment. She also said UBS will defend itself

against any charges.

After

encouraging UBS-affiliated financial advisers to increase

their efforts to sell auction-rate securities to retail

investors starting in August, the Massachusetts complaint

said, Mr. Shulman also sold much of his personal

holdings in the instruments.

Write

to Liz Rappaport at liz.rappaport@wsj.com

July

25 Front page news.

Auction-Rate

Crackdown Widens.

UBS Faces New Charges in New York, as Scrutiny of Wall

Street's Role Intensifies

By

LIZ RAPPAPORT of the Wall Street Journal

The

state of New York on Thursday joined a widening array

of prosecutors and customers accusing Wall Street firms

of wrongdoing in efforts to hold together the $330 billion

auction-rate securities market before it collapsed in

February.

State

Attorney General Andrew Cuomo filed civil fraud charges

against UBS AG, accusing the firm of a "multibillion-dollar

consumer and securities fraud," and demanding that

the firm pay back its profits from the business, make

investors whole and pay damages.

A

spokeswoman for UBS said, "We will vigorously defend

ourselves against this complaint."

The

New York attorney's case echoes a similar case brought

against UBS by Massachusetts officials and many private

cases and arbitration claims filed against UBS and other

prominent firms in recent months.

The

firms are accused of pushing risky securities on retail

and corporate customers with misleading sales tactics,

even as the market for those securities was falling

apart. When the collapse came, many customers faced

losses or were stuck with securities they couldn't sell.

Wall

Street firms themselves have suffered immense losses

and faced litigation resulting from their activities

in other kinds of troubled financial instruments --

most notably mortgage-backed securities. Their auction-rate

problem could prove a smaller financial scar than the

hundreds of billions lost in mortgage-backed securities,

but a big loss to Wall Street's reputation.

The

victims in the auction-rate cases range from individual

investors to big corporations. Some 250 public companies

held these instruments, as did tens of thousands of

individuals. The companies -- ranging from 3M Co. to

Texas Instruments Inc. -- have on average written down

the value of these holdings by 12% in the past few months,

according to Pluris Valuation Advisors LLC, a company

that helps corporations value illiquid securities. Applied

across the whole $330 billion market -- which since

February has gotten substantially smaller -- that would

amount to roughly $40 billion of losses.

Auction-rate

securities -- issued by municipalities, student-loan

companies, charitable organizations and others -- are

long-term securities that Wall Street engineered to

have short-term features. Their interest rates reset

at weekly or monthly auctions run by Wall Street firms.

The firms promised individual investors and corporate

clients that the frequent auctions made these securities

as safe and liquid as cash because they would always

be easy to sell quickly.

At

the root of these cases is a common allegation: As problems

mounted in these auctions and their own inventories

of these securities became bloated, Wall Street firms

worked aggressively to push the instruments out of their

doors and into the hands of clients, playing down the

severity of the problems rippling through the market.

The

action, Mr. Cuomo and others charge, helped to contain

their own losses but left their customers with beaten

down, illiquid investments.

The

New York complaint also alleges that several high-ranking

UBS executives, whom the New York attorney didn't name,

sold roughly $21 million of their own auction-rate securities

holdings amid the turmoil. Some 50,000 UBS customers

were left holding $37 billion worth of the struggling

investments, the complaint says.

Karina

Byrne, a UBS spokeswoman, said, "UBS does not believe

that there was illegal conduct by any employee."

After an internal investigation into personal sales

of auction-rate securities, "we have found cases

of poor judgment by certain individuals and are evaluating

appropriate disciplinary measures for these individuals,"

she said.

"It

is frustrating that the New York Attorney General has

filed this complaint while we have been fully engaged

in good-faith negotiations with his office to bring

liquidity to our clients holding auction-rate securities,"

she added.

UBS

is at the center of many of these allegations, but it

isn't alone. Investigators from 10 states showed up

at the offices of Wachovia Corp.'s St. Louis brokerage

offices last week to get documents and conduct interviews

in a dramatic escalation of their probe into its auction-rate

activities. Wachovia said it, like others, is responding

to inquiries from regulators.

State

attorneys are also probing the activities of Merrill

Lynch & Co., Citigroup Inc. and others. Merrill

Lynch and Citigroup declined to comment.

The

securities are backed by pools of other financial instruments,

such as student loans, ultra-safe municipal bonds or

complex subprime-mortgage debt. Even the safe municipal

bonds were drawn into the unfolding mortgage crisis

because they were backed by struggling bond insurers

with exposure to mortgage debt.

In

normal times, when weekly auctions of auction-rate securities

failed to generate sufficient demand, Wall Street firms

stepped in to support the market, buying the instruments

themselves. But as they became strained by other problems,

Wall Street firms stopped supporting the market with

their own bids. By February, nearly every auction wasn't

drawing enough buyers and the securities suddenly became

illiquid, impossible for investors to cash in.

In

February, the market for auction-rate securities collapsed

when the big dealers in the market -- including UBS,

Citigroup, Merrill and others -- stopped supporting

struggling auctions, leaving investors unable to sell.

Many companies have had to mark down their value, individuals

have been stuck unable to access cash, and issuers of

the instruments have had to pay higher interest rates

or find a new way to raise money.

Before

it fell apart, Wall Street firms raised some brokers'

commissions to get the securities out the door. Merrill

Lynch published reassuring research just days before

it pulled out of the market. At UBS, executives mobilized

its financial advisers to sell the securities to institutional

and retail investors, many of whom have since filed

complaints alleging UBS and others offered sugar-coated

assurances in the months leading up to the February

collapse.

One

example unearthed in the Massachusetts investigations:

Last November, Edward Hynes, an institutional sales

manager at UBS, was preparing for a conference call

with salespeople who worked directly with investors.

In an email to three colleagues who would be leading

the call, he laid out a strategy for the message that

salespeople should take to UBS clients, according to

documents filed by the state of Massachusetts against

UBS.

"We

need them to walk out and believe that this is a strong

credit w [sic] strong UBS commitment to support the

liquidity," Mr. Hynes wrote in an email to several

colleagues about auction-rate securities backed by student

loans, according to the Massachusetts case. At the time,

the market was still a few months away from breaking,

but cracks were already showing up. Mr. Hynes isn't

named in the New York complaint.

People

familiar with the email say the call would have been

with institutional salespeople, not retail investment

advisers.

"We

are not going to address specific emails taken out of

context," said Ms. Byrne in a statement. "UBS

has acted in clients' best interests in this matter."

Another

example involves a lawsuit filed early in June by Latham,

N.Y., energy company Plug Power Inc. The company claims

UBS assured Plug Power's chief financial officer, Gerry

Anderson, in a conversation in October that auction-rate

securities backed by student loans were safe and liquid,

despite spikes in their interest rates that suggested

otherwise.

Plug

Power Inc. had bought $62.9 million in auction-rate

securities backed by pools of student loans starting

in 2005, comprising 44% of its total investment portfolio,

according to the complaint. The claim alleges UBS put

Plug Power into more student-loan auction-rate securities

throughout the fall, after the CFO expressed concern.

UBS

declined to comment on the lawsuit.

Wall

Street firms started raising commissions paid to some

brokers at outside dealers who sold the securities to

clients, an action that might serve as an enticement

to them to sell more.

On

Nov. 2, 2007, for example, Credit Suisse's short-term

trading desk sent out an email informing its salespeople

that Citigroup was increasing its commissions to outside

dealers from 0.15 of a percent of the security sold

to 0.20 of a percent on certain of its auction-rate

securities, according to a person familiar with the

email. By the start of January, their commissions on

all types of Citigroup's auction-rate securities rose

to 0.15 of a percent, instead of 0.1, says the person.

Citigroup

and Credit Suisse both declined to comment.

Wall

Street analysts also put out reassuring research just

days before the auction-rate market hit a breaking point.

For example, investigators are looking at one Merrill

Lynch note that went out days before the market collapsed,

according to people familiar with several investigations.

The

note refers to problems in a $60 billion slice of the

auction-rate securities market that was issued by closed-end

mutual funds, called auction-rate preferred securities.

These auctions were faltering by the end of 2007 as

well.

"Auction

yields still attractive despite spread compression,"

reads one bullet point of the report, published by analyst

Kevin J. Conery on Feb. 8. It touted the bonds, saying

they yielded at least 0.45 percentage points more than

other types of bonds. "We continue to be impressed

by the auction market's resiliency in the face of challenging

times," the report said.

The

inside of the report notes "noise around failed

auctions," but goes on to highlight ways investors

can invest in the market most safely, and states that

securities issued by closed-end mutual funds are "still"

viewed by the firm as "the conservative's conservative

investment."

By

Feb. 13, Merrill and UBS had stopped supporting the

market.

A

call to Mr. Conery was directed to Merrill's press office.

"The research report was fair and balanced,"

says Mark Herr, a Merrill Lynch spokesman, in a statement.

"Our analyst struck the right balance between sounding

cautionary notes and concluding that there were insufficient

alarms to herald the imminent and unprecedented collapse

of the ARS market."

Write

to Liz Rappaport at liz.rappaport@wsj.com

July

24

UBS

Faces New York Lawsuit Over Auction-Rate Sales (Update4)

By

Michael McDonald and Karen Freifeld

July

24 (Bloomberg) -- UBS AG was sued today by New York

Attorney General Andrew Cuomo, alleging the Zurich-based

bank's promotion of auction-rate securities as safe,

money market-like investments was fraudulent.

Cuomo

seeks to force UBS to offer to buy back at face value

$25 billion in auction-rate securities held by

the bank's customers in New York and nationwide. Massachusetts

and Texas have filed similar complaints against UBS

since the $330 billion market collapsed in February

in an effort to force the firm to repurchase securities

it marketed in their respective states.

"We

believe we have nationwide jurisdiction, and we're looking

for recoveries nationwide,'' Cuomo said today at a press

conference in New York announcing the suit. He said

his investigation into UBS and other banks that sold

auction-rate securities is continuing, and he declined

to rule out additional complaints or criminal charges.

State

and federal regulators have been probing Wall Street's

sale of auction-rate securities since investment banks

abandoned the market in February, permitting thousands

of auctions to fail and leaving investors unable to

sell the debt. Municipalities, closed-end funds and

student loan organizations sold the long-term bonds,

and the banks ran the auctions where the interest rates

were reset every week or month.

U.S.

prosecutors and regulators are separately investigating

allegations that UBS helped wealthy U.S. citizens conceal

$20 billion in assets and evade income taxes. The company

reported a net loss of 25.4 billion Swiss francs ($25.6

billion) in the nine months through March, more than

any other bank hit by the global credit-market contraction.

"This

is something I believe can be settled because they are

not worthless; they are simply not liquid,'' said John

Coffee, a Columbia Law School securities law professor

in New York, regarding the auction-rate securities.

The investigation of tax evasion is of "an order

of magnitude more serious to them,'' Coffee said.

Cuomo

alleges in the lawsuit filed today that UBS began an

"aggressive marketing'' campaign to sell the securities

to investors as demand began to wane last year, forcing

the bank to step in as a buyer at the auctions to prevent

them from failing. UBS continued selling the securities

even as the market unraveled, with at least seven bank

executives involved in the marketing campaign unloading

$21 million in personal auction-rate holdings, the attorney

general said.

UBS

spokeswoman Karina Byrne in an e-mailed statement said

the bank will "vigorously defend'' itself against

the allegations in the suit, and "categorically

rejects any claim that the firm engaged in a widespread

campaign'' to shift auction-rate debt off its books

and into client accounts.

"While

UBS does not believe that there was illegal conduct

by any employee, we have found cases of poor judgment

by certain individuals and are evaluating appropriate

disciplinary measures for these individuals,'' Byrne

said.

The

bank on July 16 said it plans to offer to buy back as

much as $3.5 billion in auction-rate preferred shares

it sold for closed-end funds. Cuomo said today that

the offer is insufficient and that it needs to buy back

all the securities it sold.

UBS,

which closed its municipal investment banking operations

in May, was the second-biggest underwriter of municipal

auction-rate securities behind Citigroup Inc., according

to data from Thomson Reuters. It held more than $11

billion of the debt on its books when the market collapsed,

the bank has said.

Thousands

of investors have been left stuck with securities that

they thought were akin to money-market funds, facing

losses if they attempt to sell their holdings in secondary

markets, according to Barry Silbert, chief executive

of Restricted Stock Partners in New York, which operates

an exchange.

States

and local governments have refunded or plan to replace

at least $91.8 billion in auction-rate securities since

the market's collapse in February sent borrowing costs

as high as 20 percent, according to data compiled by

Bloomberg News. Closed-end funds replaced $19.7 billion

and student loan organizations less than $3 billion.

Cuomo's

complaint echoes the findings in a lawsuit filed on

June 26 by Massachusetts Secretary of State William

Galvin that attempted to show through e-mails obtained

from UBS that executives increased pressure on financial

advisers at the company to sell the securities as demand

from corporate cash managers waned. The suit alleges

the company failed to warn investors that the securities

might become illiquid, and instead continued to market

them as cash equivalents.

Galvin

is also investigating Bank of America Corp. and Merrill

Lynch & Co. More than five states participated in

a search of the securities division headquarters of

Wachovia Corp. in St. Louis on July 17 as part of a

coordinated auction-rate probe.

At

least 12 state securities regulators are probing the

collapse of the market, excluding New York, according

to the North American Securities Administrators Association.

The Texas State Securities Board this week filed a notice

of hearing to suspend UBS's state license, claiming

the bank engaged in fraud by marketing the long-term

bonds as "liquid investments.''

Regulators

in New York, Massachusetts and Texas are also seeking

damages against UBS for its sale of the securities.

Cuomo's probe involves at least 18 different banks.

The

Securities and Exchange Commission and Financial Industry

Regulatory Authority are also probing the banks. Investors

have filed about 110 arbitration claims against their

financial advisers related to auction-rate securities,

according to Nancy Condon, a spokeswoman for Financial

Industry Regulatory Authority.

UBS

said in a recent securities filing that it has also

been named in three class-action lawsuits related to

the securities.

"Certainly

the pressure is building,'' said Peter Henning, a former

federal prosecutor and law professor at Wayne State

University Law School in Detroit. "They need to

figure out a way to get the states and the SEC off its

back, then it can just deal with the customers.''

The

case is People of the State of New York v. UBS Securities

LLC, New York state Supreme Court (Manhattan).

To

contact the reporter on this story: Michael McDonald

in Boston at mmcdonald10@bloomberg.net; Karen Freifeld

in New York State Supreme Court at kfreifeld@bloomberg.net.

July

25

From

Times Online

New

York sues UBS over auction-rate securities

by

Michael Herman

Senior

bankers at UBS pulled $21 million of their own money

out of the collapsed auction-rate securities market

while continuing to tell clients their money was safe,

according to charges from the New York Attorney-General.

Andrew

Cuomo said seven UBS bankers, who have not been named,

sold their personal holdings in the three months leading

up to the collapse of the auction-rate securities market

because they knew it was heading for a crisis.

At

the same time, Mr Cuomo alleges in a lawsuit filed against

UBS in New York, the bank continued to market and sell

tens of billions of dollars of the securities to its

clients.

The

lawsuit, filed last night, does not target any individual

bankers. Mr Cuomo declined to comment on whether any

may face criminal charges as the investigation progresses.

In

a statement, UBS said that while some of its employees

had exercised “poor judgment” and it was considering

disciplinary action, none had broken the law.

The

bank said it was “frustrating” that the Attorney-General

had brought the case while the bank was involved in

negotiations to rescue the auction-rate securities market,

which collapsed in February leaving investors with $37

billion of illiquid assets.

Auction-rate

securities are a popular US debt instrument that is

held as an alternative to cash because they earn slightly

higher rates of interest but can usually be sold at

any time.

Several

large investment banks are active brokers in the $330

billion (£165 billion) market, which became a

casualty of wider credit market problems.

UBS

is facing similar charges from the state of Massachusetts

and Mr Cuomo has requested documents from other banks.

“UBS

is not alone in this scheme, we are looking at a number

of other banks.” Mr Cuomo said.

Friday

July 18

Investors

sue Bank of America over auction rate securities

St. Louis Business Journal - by Kelsey Volkmann

Investors

filed a class-action lawsuit Thursday against Bank of

America Investment Services Inc. and Bank of America

Securities, alleging that brokers deceived them about

their risk.

Bank

of America offered and sold auction rate securities

to the public as highly liquid cash-management instruments

and as suitable alternatives to money market mutual

funds, the suit alleges.

On

Feb. 13, all of the major broker-dealers, including

Bank of America, withdrew their support for the auctions,

leaving the market to crumble and investors unable to

access their money.

The

investors involved in the suit bought the securities

between June 11, 2003 and Feb. 13, 2008.

The

lawsuit, filed the same day state regulators investigated

Wachovia Securities in downtown St. Louis for its handling

of auction rate securities, is pending in the U.S. District

Court for the Southern District of Illinois.

The

lawsuit alleges that Bank of America failed to disclose

the following facts to investors:

* The auction rate securities were not cash alternatives

like money market funds but were instead complex long-term

financial instruments with 30-year maturity dates.

* The auction rate securities were only liquid at the

time of the sale because Bank of America and other broker-dealers

were artificially supporting and manipulating the market

to maintain the appearance of liquidity and stability.

* Bank of America and other broker-dealers routinely

intervened in the auctions for their own benefit to

set rates and to prevent all-hold auctions and failed

auctions.

* Bank of America continued to market auction rate securities

as liquid investments even after Bank of America and

other broker-dealers determined that they would likely

be withdrawing support for the periodic auctions and

that a freeze of the auction rate securities market

would result.

Auction

rate securities are municipal or corporate debt securities

or preferred stocks that pay interest at rates set through

periodic auctions.

The

instruments typically have long-term maturity dates

or no maturity date.

The

law firm representing the investors is Carey & Danis,

a national law firm based in St. Louis that aids represents

victims of "corporate abuse, greed and neglect,"

according to the firm.

Thursday

July 17

Super

news:

State

Regulators Raid Wachovia's Offices Looking for more

Smoking Guns on Auction Rate Securities.

Before

we get to Wachovia, let's look at what we now know.

We know that a bunch of brokerage firms deliberately

misled their clients. They told them that auction rate

securities were "cash equivalents" and you,

the client, only had to wait until the next auction

date (typically every seven days) to get 100% of your

principal back.

We

know the brokerage firms deliberately misled their customers

by not telling them of the risks that the auctions could

fail (and had failed). And we now know that virtually

every brokerage firm who peddled auction rate securities

to their clients knew there were risks and there was

a huge likelihood that the auctions would fail and their

clients would get stuck with paper securities they could

not cash out of.

Massachusetts

has discovered enough dirt on UBS to sue it for fraud

and to force UBS into redeeming $3.5 billion of ARPS.

And a bunch of state regulators are smelling dirt at

Wachovia. Based on emails and phone calls from readers

of this column, I can guess the next "bad guys"

will include Allianz, Merrill Lynch, PIMCO and Citigroup.

I'll think of a few more this evening.

Before

we get to "Why?" what's really interesting

is how many brokerage firms peddling ARPS actually deliberately

misled their own employees -- the brokers who foisted

the ARPS on unsuspecting people like you and me. (As

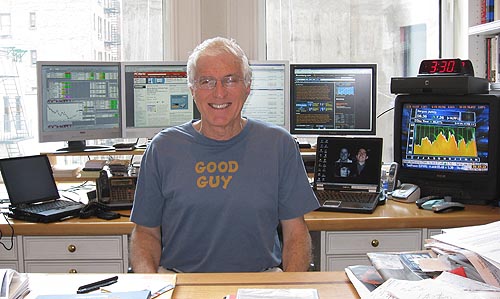

of tonight, I still have $3.3 million of ARPS.) I've

spoken to many brokers and they're livid that their

management lied to them as much as they ended up lying

to their own clients. There are many brokers out there

whom this ARPS experience has destroyed 20+year career

and left them with a really bad taste in their mouth

for Wall Street and eveything it stands for.

Now

why? Why did the brokerage firms lie to their brokers

and their customers? My take:

1.

They had ARPS on their balance sheets. They knew it

would soon be toxic and they wanted to get rid of it,

asap.

2.

They made a commission for putting their customers into

ARPS, versus putting them into money markets. They also

received an on-going commission for keeping the ARPS

into their customers' accounts -- the mutual funds pay

the same sort of fee. I believe it's called a 12b-1.

The

basic problem is that today investment banks and brokerage

firms can one and the same thing. There are horrible

conflicts of interest. For example, an investment bank

will have stuff on its balance sheet which it can't

sell to other institutions. So it chooses to sell the

crap to the clients of its brokerage arm.

You

get the message. Now to today's new. Today is a big

victory for us. Wachovia has been one of the most irresponsible

sellers of auction rate securities. -- Harry Newton

Auction

rate probe hits Wachovia

By

IEVA M. AUGSTUMS, AP Business Writer, July 17

CHARLOTTE,

N.C. - Securities regulators from several U.S. states

on Thursday raided the St. Louis headquarters of Wachovia

Securities, seeking documents and records on the company's

sales practices.

The

move is part of a broad investigation into questionable

practices involving auction rate securities, Missouri

officials said.

Missouri

Secretary of State Robin Carnahan's office said the

"special inspection" at the Wachovia division,

the former A.G. Edwards, concerned the $330 billion

auction rate securities crisis. Wachovia Securities

is part of the Charlotte-based bank, Wachovia Corp.

"Hundreds

of Missouri investors have called my office because

of inability to access their money," Carnahan said

in a statement. She added that she aims to take actions

to "to make these investors whole."

The

action, which also sought information on internal evaluations

and marketing strategies, comes after more than 70 formal

complaints were filed with the Missouri Securities Division

over the last four months, representing more than $40

million of frozen investments.

In

April, the Securities Division launched a full-scale

investigation, requesting documents, e-mails, transcripts

and other records from Wachovia Securities and other

banks.

Wachovia

Securities has not fully complied with these requests,

prompting Thursday's onsite inspection, Missouri officials

said.

However,

a Wachovia spokeswoman said, "Most securities firms,

including Wachovia, are responding to inquiries from

regulators about the auction rate securities industry."

"The

discussions that are occurring today are a part of this

ongoing process," spokeswoman Christy Phillips-Brown

said.

Wachovia,

the nation's fourth-largest bank, is the subject of

arbitration claims and a class action lawsuit that was

filed in New York in March.

In

a regulatory filing in May, Wachovia said the Securities

and Exchange Commission and other regulators are seeking

information concerning the underwriting, sale and subsequent

auctions of municipal auction-rate securities and auction-rate

preferred securities. The interest rates on such securities

are reset at regular auctions. Troubles have arisen

as demand for some high-rate securities dries up as

rates fall.

"Further

review and inquiry is anticipated by the regulatory

authorities and Wachovia will cooperate fully,"

the company said in the filing.

According

to the filing, the bank and Wachovia Securities have

also been named in a lawsuit filed in March in New York.

The lawsuit seeks class action status for customers

who purchased and continue to hold such securities based

on alleged misrepresentations concerning the quality,

risk and characteristics of the securities. The bank

said it "intends to vigorously defend the civil

litigation." ...

July

15

Galvin

Finds The Smoking Gun at UBS.

Forces UBS, The Worst ARPS peddler, to Shine with New

Virtue

by

Harry Newton

UBS

was the worst -- the company I received more emails

complaining of unfeeling UBS brokers and unresponsive

UBS management. It was the first company to write down

the value of its clients' ARPS on its clients' monthly

statements. It was the first company forced to reimburse

some of its customers -- in this case Mass municipalities

-- for selling them stuff they weren't authorized to

buy (certainly without disclosure of what they were

buying). And it was the first company to be sued for

fraud.

Internal

UBS emails discovered by William Galvin secretary of

the Commonwealth of Massachusetts contained apparently

more than enough smoking guns to sue UBS for fraud and,

I'm guessing, sufficient to force them into today's

startling development. Mark my words. UBS is not doing

this out of the goodness of its cold Swiss heart, or

out of concern for its poor suffering customers. Read

the Bloomberg story first and then we'll talk about

ramifications:

UBS

to Buy Back Up to $3.5 Billion of Frozen Shares (Update1)

By Christopher Condon

July

15 (Bloomberg) -- UBS AG, the Swiss bank being sued

for fraud over its sales of auction-rate securities,

plans to buy back up to $3.5 billion of the frozen

securities sold by its brokers and financial advisers.

UBS

clients who purchased auction-rate preferred shares

issued by tax-exempt closed-end funds can get their

money back in full along with unpaid dividends, the

Zurich-based company said today in a statement.

Massachusetts

Secretary of State William Galvin last month sued

UBS, saying investors were told the securities were

safe and easy-to-trade alternatives to cash. UBS said

at the time it will "defend the specific allegations.''

UBS

will finance the repurchases by reissuing the preferred

shares through a trust that will be consolidated on

the bank's balance sheet. The reissued shares will

carry a put option, guaranteeing the holder the right

to sell, and will be marketed to money-market funds

and other institutional investors.

To

contact the reporter on this story: Christopher Condon

in Boston at ccondon4@bloomberg.net.

Last Updated: July 15, 2008 17:06 EDT

You

can read the entire UBS release. Click

here.

Now

here's today's UBS story from Dow Jones:

UBS

Plans New Security To Rescue Auction-Rate Shareholders

By

Daisy Maxey of DOW JONES NEWSWIRES

NEW YORK (Dow Jones)--UBS AG (UBS), which is facing

increasing fallout as a result of its sales of auction-rate

securities, said it's working to create a structure

that would allow it to buy back auction-rate preferred

shares.

The

bank is working to develop Trust Preferred Securities

with a liquidity put or similar demand feature. The

new product would permit it to offer to purchase all

auction preferred stock issued by registered closed-end

tax-exempt funds held by eligible UBS advisory and

brokerage clients in UBS accounts at par.

The

new securities, which would be issued in one or more

private placements by the trust, are meant to be eligible

for purchase by money-market funds. The liquidity

feature would be provided by UBS or another highly

rated bank, UBS said in a statement.

UBS

clients hold about $3.5 billion of auction-rate preferred

stock issued by registered closed-end tax-exempt funds

in UBS accounts, the bank's statement said.

Municipalities,

mutual-fund companies, nonprofit institutions, corporations

and student-lending companies borrowed money in the

$330 billion auction-ratesecurities market, where

they obtained long-term financing that had the features

of short-term securities. The rates reset periodically

in auctions conducted and backed by Wall Street firms

until the second week of February, when dealers stopped

supporting the market. Investors were then left stranded

with no way to sell their auction-rate shares.

UBS

is likely anxious to find some liquidity for its clients.

In

June, Massachusetts Secretary of the Commonwealth

William Galvin's office charged UBS Securities LLC

and UBS Financial Services Inc. with fraud for offloading

millions in auction-rate securities to retail clients

as a way to clean out its inventory once it was clear

that the auction market was in trouble. Other states

may follow, and the Securities and Exchange Commission

and the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority are

also looking into sales of auction-rate securities

to retail clients by various firms.

Implementing

the proposed security is dependent on a number of

factors, including legal requirements, UBS said. The

bank said it has been working for several months to

develop the structure and has obtained guidance from

the Department of Treasury in relation to tax considerations,

and met with staff of the Securities and Exchange

Commission regarding aspects of the proposed structure.

It

expects that offers to purchase the auction-rate preferred

shares will come within about 30 days of resolving

regulatory issues.

The

proposed securities appear to be similar to those

planned by sponsors of closed-end funds, including

Eaton Vance Corp. (EV), Nuveen Investments and BlackRock

Inc. (BLK). Whether money-market funds will be willing

to purchase any versions of such securities remains

to be seen.

UBS

had faced mounting concerns due to its sales of the

securities. In addition to the scrutiny by Galvin's

office, UBS Financial Services settled with the Massachusetts

attorney general's office in May to return $37 million

to the Massachusetts Turnpike Authority and 17 municipalities

that invested in auction-rate securities after the

firm agreed that the securities weren't permissible

investments under their official investment mandates.

In

addition, an investor has filed an arbitration claim

against UBS Financial Services Inc. and the global

head of its Municipal Securities Group, David Shulman,

seeking the return of $2.5 million now frozen in auction-rate

securities along with punitive damages for alleged

fraudulent sale of the shares. The claim, filed with

the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority by New

York law firm Stuart D. Meissner LLC., alleges that

the division of UBS misled investors by not providing

material information regarding the liquidity risks

of such securities.

And

Timothy Flynn, a financial advisor who sold millions

in auction-rate securities to municipalities while

working for UBS Investment Services Inc., filed a

federal whistle-blower complaint with the U.S. Department

of Labor against the firm in mid-June, alleging that

he faced retaliation after cooperating with a Massachusetts

investigation into the sales.

-By

Daisy Maxey, Dow Jones Newswires; 201-938-4048; daisy.maxey@dowjones.com

As

to ramifications?

1.

UBS obviously believes it can sell the re-morphed securities

to money-market funds. If they can do it, then all the

issuers -- like Nuveen, BlackRock, Eaton Vance, etc.

-- can also do it. This should speed up the whole redemption

process.

2.

UBS is only one of around nine or so brokerage firms

whose auction rate securities sales practices are being

investigated. I bet there's dirt on all of them -- conversations

and emails they don't want revealed publicly on low-class

web site (like this one). Hence I'm hoping that they'll

all choose valor over secrecy and get us our money back

ASAP. Are you listening Deutsche Bank and Nuveen (the

two perpetrators of the $3.5 million of ARPS I still

am stuck with)?

3.

None of this relieves any ARPS owner (that's you and

me) of the obligation to continue putting pressure on

his brokerage firm, his ARPS issuer... and letting his

local attorneys-general and others know also. You might

also drop Paulson and Bernanke a letter telling them

you can't spend money you can't get to. Until you can

get to it, the economy will suffer.

+++++++++++++

Regulators

press Wall Street to help revive auction-rate securities

By

Joanna Chung, Francesco Guerrera and Ben White in New,York

Published:

July 14 2008 03:00 in the Financial Times (the pink

paper)

Wall

Street banks are coming under growing pressure from

US regulators to help unfreeze the market for auction-rate

securities, one of the biggest casualties of the credit

crunch.

Officials

from the enforcement division of the US Securities and

Exchange Commission are talking to a number of banks

in an effort to find solutions to restore liquidity,

according to several people briefed on the matter.

The

discussions are focusing on parts of the $330bn (€207bn)

market that have affected retail investors unable to

access their investments since liquidity started to

dry up in February.

The

SEC has floated the idea of large players in the auction-rate

securities market, such as Citigroup, Merrill LynchUBS

and Morgan Stanley, buying back some of the securities

at their original price, several people said.

However,

the plan is being resisted by several banks. They argue

that holding such illiquid securities, whose price has

fallen sharply, would lead to further writedowns and

losses, worsening their financial plight and depleting

their capital base.

"The

auction-rate market will be dead for a long time and

the last thing we want to do is hold this stuff on our

balance sheet," said one senior banker.

The

SEC, which is among the regulators investigating how

the securities were sold to investors and whether they

were informed of the risk they could become illiquid,

declined to comment, as did the banks.

However,

people close to the situation say some banks are willing

to devise a solution, not least to avoid draconian

actions by regulators and to limit reputational damage.

Many

investors have treated auction-rate securities as they

would cash deposits or money market accounts. While

the securities are long-term debt, interest rates are

periodically reset at auctions supported by banks.

But

the sector started to falter as dealers stepped back

and stopped taking on unsold securities in auctions

they managed.

A

dozen state securities regulators and Andrew Cuomo,

New York's attorney- general, are conducting inquiries.

Nearly all the leading investment banks are the subject

of investigations into the auction-rate market's failure.

More

than half of the outstanding securities have been refinanced

or bought back by the issuers, according to industry

sources. (This is not true. HN)

Harsh

lesson in student lending

By

Michael McDonald | Bloomberg News

July 14, 2008

Five

months after the collapse of the $330 billion auction-rate

securities market, bonds backed by student loans show

no signs of recovering. And that means no new house

for Martin Doolan.

The

former corporate turnaround executive delayed buying

a home in Dallas because he can't access the $4.85 million

he has in student loan auction-rate bonds without selling

them at a loss of at least 20 percent. Doolan said he

bought the securities over the past two years through

Zurich-based UBS AG because they were billed as easy

to turn into cash, like money market funds.

"I

was advised these were the safest" of all the auction-rate

securities, said Doolan, 68, who declined to identify

his financial adviser at UBS.

Kris

Kagel, a spokesman for UBS, said the firm doesn't comment

on individual cases, though it is "working with

clients on a case-by-case basis to address their immediate

liquidity needs," including offering loans.

The

$85 billion of auction-rate securities sold by state

agencies and private lenders to finance student loans

are emerging as the most toxic type since Wall Street

dealers abandoned the auction-rate market in February

amid worries about the financial health of the bond

insurers who guaranteed the debt.

The

auctions—held every seven, 28 or 35 days to set

interest rates on the student loan debt—fail about

99 percent of the time, leaving investors with no choice

but to take discounts to get out of the bonds.

Companies

that hold student-loan auction-rate securities wrote

down the value of the debt this year, some by as much

as 35 percent, according to a survey by Pluris Valuation

Advisors LLC. More than two-thirds of the publicly traded

companies tracked by Pluris marked down the debt, compared

with half that took a loss on their municipal auction-rate

debt or securities sold by closed-end funds.

"The

entire issue is one of lack of liquidity, and the very

poor returns," said Espen Robak, president of Pluris,

a New York-based firm that helps companies place values

on their holdings.

Auction-rate

bonds, invented about two decades ago, allowed local

governments, hospitals and universities to borrow money

for the long term at cheaper, short-term rates.

Until

mid-February, banks supported prices by bidding for

bonds that went unsold. Once the banks stopped buying,

interest costs soared as high as 20 percent because

the failed auctions triggered a penalty rate for issuers.

While

rates on student loan securities initially rose, they

have ultimately fallen because the bonds contain provisions

that prevent rates from rising for an extended period

of time. The solvency of the lenders is dependent on

their ability to borrow at lower rates than those at

which they lend.

According

to Moody's Investors Service, more than half the student